Rachel Whiteread: The interview between sculptor Rachel Whiteread and Bice Curiger entitled The Process of Drawing is like Writing a Diary: It’s a Nice Way of Thinking About Time Passing. Reflect on the references Whiteread makes to drawing.

Claus Oldenberg: Investigate Claus Oldenberg’su’s Manhattan Mouse Museum and consider the relationship of his collections to his work.

Eduardo Paolozzi: Research his processes and use of the studio as a repository for the objects he accumulated and collected online and in books.

Hanne Darboven: German artist Hanne Darboven originally trained as a pianist but turned to painting, pursuing work that took systems such as calendars and reproduced them in grid-like forms using handwritten symbols.

“Research three artists listed above and one other practitioner whose work centres around collecting and archiving online and in books. In your learning log, record your findings by considering approaches and methodologies that might resonate with your strategy and the development of the body of work. Considering your choices and preferences concerning materials, subject matter, colour, use of objects, etc., how would you archive your own work and processes? What methods of classification would you use? Could you classify in terms of date found or created, colour, and type of object? What might the process of archiving bring to your work? Might these processes help you title the work or allow an audience to party to your working processes?” (Advanced Practice coursebook p.52)

Eduardo Paolozzi ( 1924-2005)

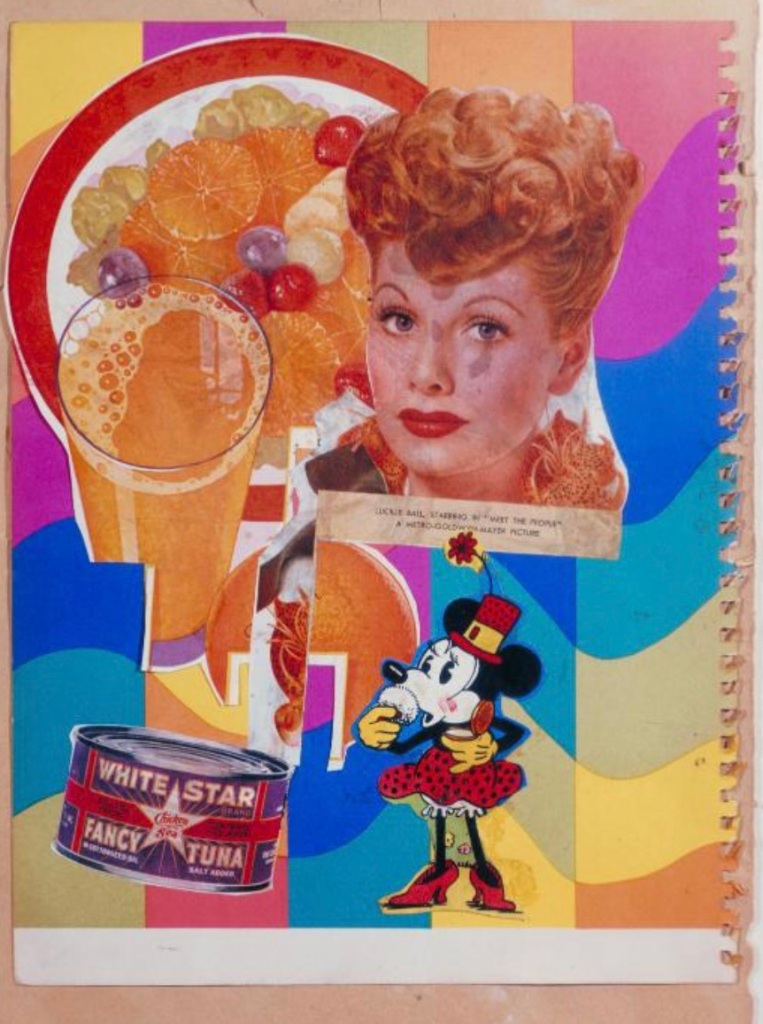

Sir Eduardo Paolozzi is an Italian-born Scottish visual artist famous for his sculptures, collages, murals, and prints. He was influenced by the DaDa and surrealist movements and was also interested in technology and science. His “Bunk!” series of collages is recognised as a prototype of Pop Art. He created these collages with cut-outs from American magazines, a technique he discovered when he was a child growing up in Scotland.

Below are some of his collages from the “Bunk!”, from left to right: “Meet The People”, 1948; “Sack-o-sauce”, 1948, images via http://www.tate.org.uk;

Another notable work of his is the murals at Tottenham Court Road, which were completed in 1984 after being commissioned by London Transport in 1980.

Eduardo Paolozzi’s mural at Tottenham Court Road Station,photo my Roger Marks, image via http://www.thebeautyoftransport [accessed on May 17th. 2024];

Below are some of his artworks, from left to right: Newton, Master of The Universe, Sir Eduardo Paolozzi, bronze, 1988; Mayan Dog, Sir Eduardo Paolozzi, 1985; Mondrian Head, Sir Eduardo Paolozzi1989; images via http://www.tate.org.uk [accessed on May 17th 2024];

Paolozzi’s practice of collecting things and objects for his ready-made artworks inspired me to try it myself. His artworks were in anticipation of consumerism, as he confessed that he wants to use everything he finds good; he doesn’t discard things such as a nice wine bottle or a nice box. I also have an eye for beautiful, ready-made things, and I also have this instinct of “not throwing them away,” so I will try to use them for my artwork.

Rachel Whiteread (b.1963)

I have read the the interview between sculptor Rachel Whiteread and Bice Curiger entitled The Process of Drawing is like Writing a Diary: It’s a Nice Way of Thinking About Time Passing online https://www.tate.org.uk/tate-etc/issue-20-autumn-2010/process-drawing-writing-diary-its-nice-way-thinking-about-time-passing

In this interview, she emphasises the importance of her drawings: “My drawings are very much part of my thinking process. They are not necessarily studies. I use them as a way of worrying through a particular aspect of something that I’m working on. Quite commonly, there will be a dozen or so drawings of more or less the same thing.” I must confess that for me, it is difficult to consistently study one object repeatedly. However, I try to stick to this creative routine since I observe how beneficial it is for the outcome. Like many other visual artists, she practices collecting various objects in her studio. She is attracted by the strange, bizarre, unusual objects. I understand she collects them just because they catch her attention, but she has no creative idea yet. I reflect on her approach and see that I am not keen on finding beauty in strangeness. Moreover, I always judge useless objects as rubbish, thoughtlessly produced by someone with no artistic pursuit, greedily chasing quick profit from thousands of headless consumers. When asked how she keeps the objects, she answered: “In the studio, there is no real logic to it.” Thus, Rachel Whiteread doesn’t have a special approach to cataloguing and sorting them out. I watched a good video with her, giving an interview in her studio in London. She has a very different attitude to things/objects, sharing that her favourite place to check are dumps and second hand shops since she was a child. Rachel Whiteread is a rare woman who works with metal and concrete. Watching and listening to her interview, I understood that she is much like an engineer; she likes to experiment with her cooking process and get new things/objects. She says she likes materials and loves to play with them.

Below are her artworks I resonate with:

Poltergeist, Rachel Whiteread, 2020, corrugated iron, beech, pine, oak, household paint, and mixed media. Photo Prudence Cuming Associates, image via http://www.gagosian.com;

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

It was interesting for me to research Pablo Picasso’s archiving approach. The best article about his practices of accumulation and archiving is on the Musee Picasso Paris website. It is mentioned in the article on the Archive page:

“The written archives are made up of more than 100,000 documents. Collected from Picasso’s various homes, the archives contain self-penned texts, personal papers, accounts, books, exhibition catalogues as well as correspondence, author manuscripts, publication proofs, tracts, invitation cards, press clippings and more: the palimpsest of a full life by this artist known for “keeping everything”.“

Picasso was very keen on photography, and his reference material collection is massive: “The photographic archives comprise over 17,000 documents and bear witness to Picasso’s often experimental interest for the medium of photography.” (The Collection, http://www.museepicasso.paris). In her article for BBC about Picasso, Daisy Dunn said: “Picasso would have little time for today’s neat and minimalist interiors. He surrounded himself with clutter, knowing that even the tatty, mundane items other people threw away could have artistic interest. He hoarded everything, from old newspapers, scraps of wrapping paper and used envelopes to packets of tobacco, bus tickets and paper napkins. When his piles of papers grew too high for his table tops, he would clip them together with bulldog clips and suspend them, chandelier-like, from the ceiling.” She also refers in the same article to Picasso’s saying: “You are what you keep”. However, Picasso was known for his habit of recording things. I found some photos of Picasso working in his studio, and it is seen there that he kept his works around him in the studio, reflecting on them during the creative process. Even though we can see his studios cluttered with a massive gathering of all sorts of materials he used, Picasso was known for managing his collection of artworks and materials. He dated his works, allowed photographers to take photos of his studios to document the content, employed assistants and relied on family members to help manage his studio and materials.

My reflection on archive practices.

My observation of the archiving practices of such prominent artists as Francis Bacon, Rachel Whiteread, Eduardo Paolozzi, and Pablo Picasso led me to one obvious conclusion: all these artists are fanatical about gathering things. The artistic attitude to accumulating materials is a “things gathering disorder” with a spectrum, where all artists have their own place. I can mention Gerhard Richter (b.1932-), whose artistic studio practice I researched in the previous part. G. Richter is known for his super neat, clean, minimalistic studio because he doesn’t want to be distracted by anything from his work. At the polar end of the spectrum is Francis Bacon’s absolute chaos in the famous studio. All of the others are in between:)).

Speaking about me, I don’t have a massive collection and haven’t faced a problem with materials management yet. However, I see where I am heading. My materials are organised in the following groups:

- Photographs of flowers, plants, and skies make up the majority of my reference materials. Most of them are stored in the cloud, but I think I need to organise them in folders by plant type.

- Books with illustrations and about famous artists are thick, heavy, expensive, and often rare, with limited editions. I keep them close to me in my office.

- Paper and paper products such as paper placemats, prints, pieces of wallpaper, Japanese and Korean painting paper, and postcards are kept on the stack.

- Botanical material: Dried leaves and pieces of tree bark. I keep them in separate paper envelopes in the box.

- My works. I keep sketches and less significant works in the large carton folder. I keep solid work around me since they help me think and move forward.

I resonate more with neat and clean approach, too much chaos and clutter makes me feel unproductive and unbalanced. I clean my working space and arrange stuff on surfaces around me regularly, almost every week. At this stage of me as a visual artist I am not interested in collecting various material objects, I am not fascinated with things. It is mostly determined by my spiritual approach to material. Everything is temporary. Things remind me of the suffocating bondage of our material existence on this Earth, which I want to break and get rid of. Thus I am not inspired by beautifully crafted objects, bizarre and strangely made, new ones or discarded. I feel enchanted with the colour of the Sunlight at certain moments after it rises, the colour of the sea near me, and the tree’s foliage every time of the year. These things can not be placed, accumulating dust in the studio, they stay in your head, in your emotion.

Bibliography: “Sir Eduardo Paolozzi (1924-2005)”, RA Collection: People and Organisations, online on https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/name/eduardo-paolozzi-ra [accessed on May 16, 2024]; “Sir Eduardo Paolozzi (1924-2005), Tate Museum, online on https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/sir-eduardo-paolozzi [accessed on May 16, 2024]; Eduardo Paolozzi, Scottish, National Galleries of Scotland, Introducing Art and Artists, Youtube, online on https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/artists/eduardo-paolozzi [accessed on May 16, 2024]; “Eduardo Paolozzi: Underground Artist’, December 13, 2017, online on http://www.thebeautyoftransport [accessed on May 17th. 2024]; Artist Rachel Whiteread: “Artists reflect on what is happening”, Louisiana Channel, June 2022, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9436JCNqsmk [accessed on May 17th, 2024]; Pablo Picasso, Archive, Musée Picasso Paris, online on https://www.museepicassoparis.fr/en/collection [accessed on May 18th, 2024]; “The Chaotic Habit Behind Picasso’s Genious Work”, Daisy Dunn, 17 February 2020, BBC online on https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20200214-the-genius-of-picassos-hoarding-habit [accessed on May 18th, 2024]; “Previously Unpublished Pics of Picasso in His Studio”, Hyperallergic, Claire Voon, February 19, 2016, online on https://hyperallergic.com/270525/previously-unpublished-pics-of-picasso-in-his-studio/ [accessed on May 18th, 2024]; How Pablo Picasso archived the materials in his studio?, Chat GPT, [accessed on May 18th, 2024];