Japanese visual arts traditions influence Western Modern Art.

Introduction:

In my critical writing essay for Part 6, Painting Two course, I will discuss ideas of Japanese visual art traditions and their influence on early European modern art, such as Impressionism and Symbolism in the late XVII – end of the XIX century.

I resonate greatly with Japanese Art and European Impressionists, Symbolists and Post Impressionists artworks. However, though I have many favourite artists, Gustav Klimt and Katsushika Hokusai stand out. Thus, writing this essay was an excellent opportunity for me to study their artistic legacy and talent. Of course, the influence was mutual afterwards: Japanese painting artists were influenced by European painting traditions as well, but in this paper, I focus on the followings questions:

How did Japanese paintings influence European Modern Art and Impressionism in particular?

How did famous European impressionists implement new approaches in their impressionist paintings after they discovered the Japanese visual artworks Ukiyo-e?

Was Japanese visual art more sensual or sensual in a different way?

Historical reference.

Japan for many centuries stayed as a very isolated society. It must be said that for almost 200 years, between 1641 and 1853, only the Dutch were exclusively allowed by Emperor to trade with Japan. Thus many Japanese artefacts started to come to Europe via this trading channel. In 1854, the Kanagawa Convention opened the trade between Japan and the West on a larger scale. Even though the Treaty’s political background was complex and difficult for Japan, that event became the country’s first and most massive start to promote its culture to the West and worldwide in the last 200 years. It is a well-known fact that most of the leading Impressionists of the XIX century, including Edgar Degas ( 1834-1917), Mary Cassatt (1844-1926), Claude Monet (1840-1926), Camille Pissaro (1830-1903), James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), and even Post-Impressionists like Henri Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901), Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890, Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), as well as Austrian symbolist painter Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) and French modernist painter Eduard Manet (1832-1883) were deeply impressed by Japanese visual arts such as ukiyo-e woodblock prints. For example, Edgar Degas, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin,Édouard Manet French sculpture Auguste Rodin ( 1840-1917), Gustave Klimt, collected works of Katsushika Hokusai in particular. Edgar Degas was especially impressed by Hokusai’s figurative drawings of non-posed, ordinary life activity human figures.

I suggest if we want to understand why Impressionists were in admiration of new exotic images and paintings, it is essential to examine what they saw, started to collect and study. Tsoumas, J. in his paper “The Japanese Artifacts Display at the 1862 Great London Exposition: an overview”, precisely formulated the idea of Japonism’s aesthetic phenomenon in Europe. “In this paper we will examine in what ways the newly term of Japonism celebrated exoticism, sensuality and novelty as it not only represented the original and pure handicraft of the Far East tradition, but also constituted a matter of fundamental significance for the birth of a new aesthetic and cultural trend which shaped the European arts and design of the rest of the nineteenth century.” (Tsoumas, J., 2017, p.23).

Part 1: Exoticism and new concepts in design.

The first notable exhibit of Japanese artefacts occurred in 1862 at the Great London Exposition as a display of a private collection of Sir Rutherford Alcock (1809-1897), British Minister to Japan. As a keen collector, he managed to assemble a vivid array of different Japanese beautifully handcrafted objects from different historical periods and social origins; as Tsoumas J. describes it: “The collection included art products such as wonderful woodblock prints by famous and unknown artists, beautiful silk kimonos, ceremonial masks and valuable porcelain objects which were mixed harmonically with the vernacular straw raincoats and hats of Japanese peasants, rural work clothes, straw shoes, lanterns and other objects of daily use” (Tsoumas, J. 2017, p.28).

Two simple but powerful observations about Japanese design and aesthetics struck the audience: a) deep emotional connection to nature, resulting in a purity of forms and sensuality; b) superb quality of craftsmanship, expressed at most production levels and social origin. At the time of the industrial revolution in Great Britain and Europe, superior quality was directly related to the level of industrialization, and Fine Arts had been standing out. There was a significant distance between daily life objects of artisan origin and industrially produced items. At the same time, Japanese artefacts were truly remarkable because each artisan piece possessed high aesthetic value. Though Japan was not a highly industrialized country then, its design concepts and aesthetics of everyday life objects were of a very high aesthetic standard.

Let’s narrow our discussion to Japanese visual arts objects proliferating to Europe to the great admiration of Western artists. Most of these objects were Ukiyo-e woodblock prints. Interestingly, even though the first exhibits of Japanese artefacts took place in London, it was mainly France, where artists became deeply enchanted with new artistic approaches in visual arts. Ukiyo-e prints proliferated into small Parisian art and bookshops. For example, Van Gogh started collecting them and organized a Japanese print exhibition in Paris in 1867. That “Paris Exposition Universelle” presented Japanese artefact at a much larger scale and was where many purchased their first prints. Claude Monet keenly collected many Japanese woodblock prints, still hanging in his Giverny home. As it is mentioned on the website “Fondation Claude Monet”,: “Claude Monet’s collection is composed of forty-six prints by Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806), twenty-three by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and forty-eight by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858), that is to say one hundred and seventeen out of the two hundred and eleven exhibited, plus thirty-two prints held in reserve.” (s.d. http://www.fondation-monet.com/japanese prints/). It is worth noting that mass produced ukiyo-e drawings were not highly valued in Japan. Most rich Japanese still considered them as low class commercial art, preferring classical artworks from ancient Kano and other schools. When the massive trade began from the Kanagawa treaty, ukiyo-e paintings were used by the Japanese as wrapping paper for traded goods to fill the space in trade packaging.

What is Ukiyo-e (1672-1880)

The term “Ukiyo-e” is usually translated as “pictures of the floating world” or “pictures of the changeable world”, which refers to Edo Period Japanese paintings and woodblock prints that initially depicted the cities’ pleasure districts. This peaceful historical period of Japan is notable with prevailing ideas of sensual pleasures of life, encouraged amongst a tranquil existence and serene natural environment. Therefore, these prints reflected leisure activities with Japanese beauty aesthetics, incorporating poetry and spirituality, depicting scenes of nature, and daily life, including love, eroticism and sex. However, one of the most distinguished art critics and scholars of Japanese visual arts, Matthi Forrer, finds the “the floating world” popularly applicable to Ukiyu-e woodblock meaning as not wholly correct. He says: “It was often said that while people in Osaka strove to become wealthy, in Edo the aim was to spend one’s earnings the same day. It was this approach to life, always enjoying today and worrying about tomorrow, that was the true spirit underlying these pictures “of floating world” ukiyo-e- a term often incorrectly applied to all Japanese woodblock prints in Edo period”.(2008, p.18).

Ukiyo-e was known for several genres, subject to what type of activities or objects they represented: These included bijin-ga, shunga, yakusha-e, kacho-ga, and landscape. Bijin-ga, what means “beautiful person picture,” was a major genre of ukiyo-e, mainly devoted to female figures. The term shunga can be translated in Japanese as “pictures of spring,” as spring was related to sexual pleasure and sensual arousal. Yakusha-e, or “actor pictures,” were prints depicting kabuki actors, deliberately made in inexpensive single-sheet drawing to promote theatrical performance.

Another dominant genre of ukiyo-e was kachō-ga or “bird and flower” paintings, a style initially strongly influenced by the traditional Chinese genre of flowers, birds, fish, and insects. The negative space- blank space was an essential element of kachô-ga, outlining the idea of selecting only a single species of bird paired with a single plant and leaving much of the surrounding space unpainted to emphasize the details and uniqueness of the object.

It is worth mentioning an array of Japanese Ukiyo-e artists: Hishikawa Moronobu (1618-1694), Suzuki Haronobu (1724-1770), Torri Kionaga (1752-1815), Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806), Tōshūsi Sharaku (flourished 1794-95), Katsushika Hokusai (1791-1848), Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798-1861), Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1861), Hashiguchi Goyō (1880-1921). These artists worked in different times and genres of the Ukiyo-e movement, significantly contributing to its development and flourishment.

Discussion.

Before we take a closer look at particular works, it is essential to review some notable features of Ukiyo-e paintings.

The following artistic features characterize them: deploying aerial or unusual perspectives, lack of chiaroscuro or depth; use of subtle colours, softness and the restricted palette of a few primary colours; or elaborate patterns, rich intense black, red and sometimes gold; floating, ungrounded objects, such as cloth or objects of nature; superb mastery of lines, curvy and linear forms along with contrasting sharp horizontal and vertical lines; a unique sense of form and structure; depiction of naturalism of ordinary activity in every day, often communal, life; individualized poses of characters; emotion, erotism, intimacy;

In his essay “Claude Monet and Japonism, Chris Morrison described: “Certain standard devices and themes found in Japanese prints were particularly attractive to Western artists. Among them were: an unusually low or high perspective, an original use of colour, distinctive decorative patterns on clothing, asymmetrical compositions, strong diagonals, stylization, and the use of silhouettes in the background.” (www.thirty-twominutes.wordpress.com)

Another important aspect is the subject matter, which appeals to impressionists and has become a common ground for Japanese and western artists. Impressionists appreciated painting daily life scenes, ordinary life activities and experiences, and their surroundings, such as busy streets, bridges, sailboats, riversides, social gatherings, etc. They found the same subjects, which fascinated the Japanese as well.

Everything abovementioned can be classified as an unconventional approach to painting traditions established in the West by that time. Impressionists were well known for their existential struggle with rules and norms in visual arts, particularly from Academie des Beaux-Arts, an establishment that held the salons. As art critic Kelly Richman-Abdou explains in her article for My Modern Met platform: “The salons tended to favour conventional, mythological, and allegorical scenes- rendered in a realistic style” ( June 12, 2019).

Probably, Claude Monet’s saying of Japanese paintings in June 1909, in his interview for Gazette des Beaux Arts summarizes in the best way impressionists’ impressions: “If you absolutely must … find an affiliation for me, put me with the Japanese of old: the refinement of their taste has always appealed to me, and I approve of the suggestions of their aesthetic, which evokes the presence by the shadow, the whole by the fragment.” (Morrison, C., 2019, Claude Monet and Japonism)

What was the difference between Japanese and European visual art creative approaches and methods by that time?

Western classical art’s rule was always about utilizing the illusion of creating three-dimensional space, while Japanese art focuses more on bold outlines and flat regions of colour. Still, bold outlining in painting and drawing is not considered a good drawing gesture. In addition, the medium for Asian art was typically thin rice paper or woodblocks, while Western paintings are usually oil on canvas. Although both traditions used woodblock printing, they used different mediums. Japanese visual artists used water-based inks, while Western artists opted for oil-based inks. That one difference in medium produced a dramatic visual effect: water-based inks give a unique lightness and transparency, contributing to the development of the “floating” effect and a unique perspective. Ink also allows the introduction of multiple transparent layers. Another ink’s value, fluidity and smoothness, heavily emphasized superior linear skills rooted in traditional calligraphy.

Part 2.

How did European impressionists and post-impressionists address new ideas in their artworks?

These new ideas the westerners found in Japanese paintings and experimented with usually is considered in three main directions: the subject matter, the colours, the technique, including the composition and overall design and linear technique.

Below I will focus on some particular works of Gustav Klimt and Claude Monet to illustrate how I see the influence of Japanese paintings on western Impressionism.

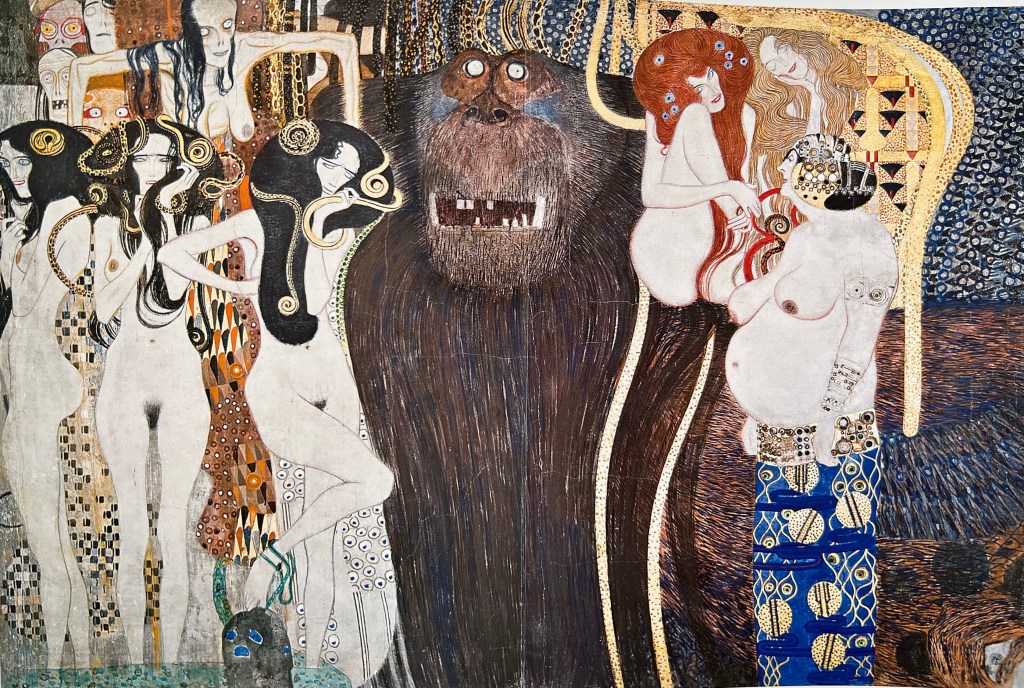

I find a lot of parallels between Gustav Klimt’s famous series of paintings, “Friese Beethoven, 1901-1902”, the central piece “The Hostile forces and Three Gorgons” (below), and Katsushika Hokusai’s ” Tametomo and the Demons of Onigashima” (1811-1812).

Even though we can’t know whether Klimt ever saw this particular Hokusai painting, I find many interesting and exciting features they share. For example, both images contain demonic figures painted in strong solid colours and lines. In addition, they both illustrate the challenges of human existence as a struggle with powerful evil forces. Both artists emphasize the eyes of these creatures in the same manner, making them white with black dots on their eyeballs, which translates to viewer emotions of fear and the inevitable presence of evil in life. The central figure in Klimt’s painting is a giant monster, resembling a gorilla, painted with many long black lines. The surrounding figures of three Gorgones and other female images are outlined with curvy lines. We can observe the same approach in Hokusai’s figures in his painting. Both paintings contain rich geometric patterns occupying negative space and cloth of demonic subjects. Evil is represented by figures put in a dense, crowded position.

If we look at Hokusai’s painting “The Plate House” from the series “One Hundred Tales”, 1831/1832, colour woodcut (below), we can find a striking resemblance of female facial features with those in Klimt’s painting above. The faces are pale, ashen shade and narrow, with black, outlined eyes and massive black hair. The same resemblance I find in the painting by Kawanabe Kyōsai, “Fantôme”,1883, silk painting (below): the facial expression, the shade of skin, narrow, anorexic body.

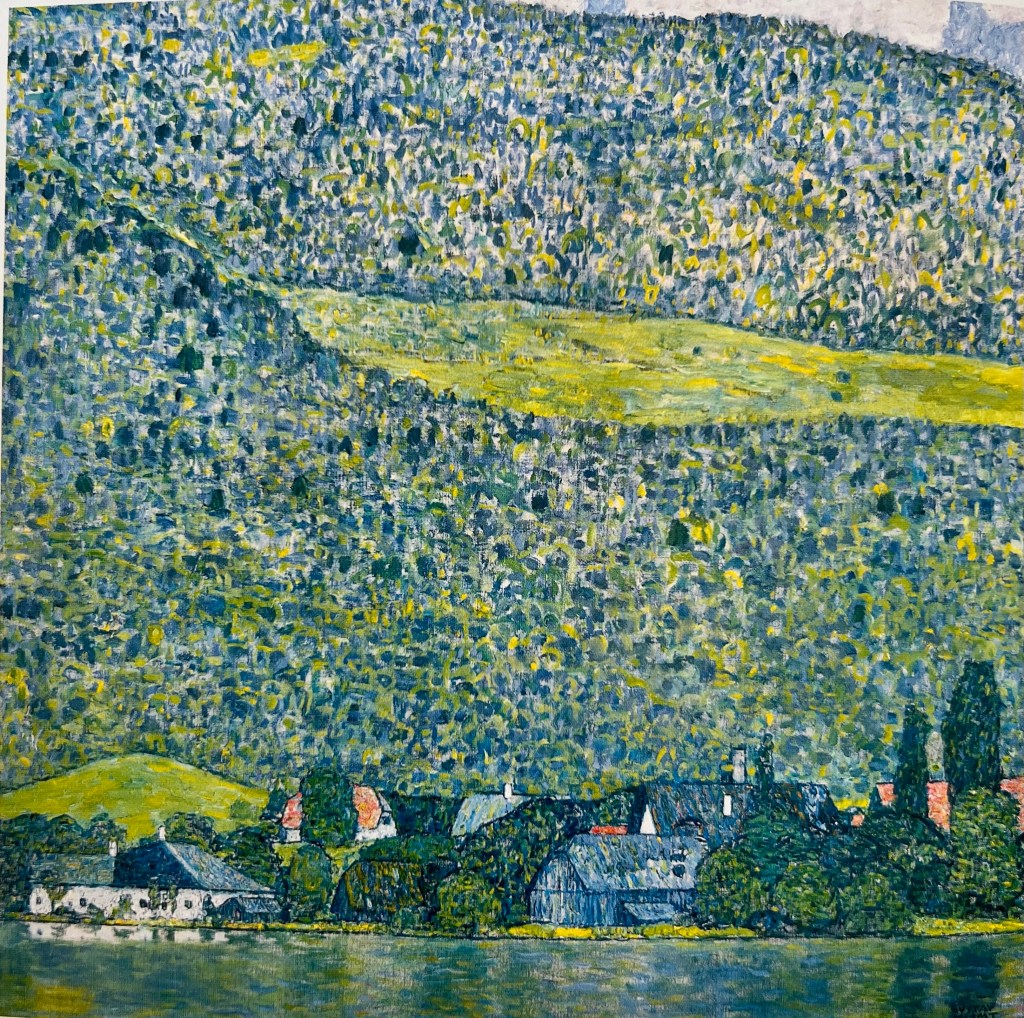

Another example in my discussion are landscapes of Hokusai and Klimt. Let’s look at their works, such as below:

“Snow on the Nose in Settsu Province”, Katsushika Hokusai, 1830-1834, colour woodcut, on the left; and “Moon over the River Yodo in Settsu Province”, Katsushika Hokusai, 1830-1834; colour woodcut; below on the right.

As well as at landscapes : “Maisons a Unterach am Attersee”, Gustav Klimt, 1916, oil on canvas- below on the left ; and “Litzlberg sur L’Attersee”, Gustav Klimt, 1914-1915, oil on canvas; below on the right.

Another addition to view in this line is the “Landscape at Le Cannet”, 1928, by Pierre Bonnard;

These paintings contain the same approach to overall composition and perspective. The sense of perspective is flat; we can see that objects are placed vertically, one on top of another, in complex, uneven layers.

Another landscape painting in the line of my discussion which stands out is Van Gogh’s “Landscape with House and Ploughman”, 1889, oil on canvas, below on the left. I find this landscape a powerful painting created against all traditional rules of perspective. The viewer’s point is lifted up, so we can view the patchwork of land plots as we do so in the aeroplane. This viewing point is typical for Japanese landscape paintings, where we can have this panoramic view of details on the surface. A good example is below : “The Old Shrine in Shiogama and The bay of Matsushima from a Bird’s-Eye-View”, 1824-33, Katsushika Hokusai, colour woodcut; below on the right.

I want to draw your attention to one landscape below created by Tawaraya Sōtatsu, “Cerisiers et Coretes du Japon”, painted on paper at the beginning of the XVIII century. It is strikingly modern! The way he did the cherry flowers in blossom, the thick and robust stems of trees, the geometric elements of the composition, the large flat block of colours- everything looked like modernist art in Europe.

Regarding the landscaping painting, I would like to bring up one more point for discussion. I have found a fantastic landscape painting created by an anonymous Japanese artist in the XV century below.

It looks very impressionistic, and I see a lot in common with Claude Monet’s landscapes below:

“Le Parc Monceau”, Claude Monet, 1876, oil on canvas; and “Bordighera”, Claude Monet, 1884, oil on canvas.

We can see the same artistic attempt to catch the wind and nature’s constant moving flow through numerous different sizes and colour dots, tiny brushstrokes scattered diagonally all over the surface. Furthermore, both artists place all elements of their paintings in strong relation to each other, creating no borders between them, or overlapping them, which makes the whole image versatile in detail but very united in one entire visual phenomenon.

In this essay, I don’t bring into discussion some works such as Van Gogh’s Bridge in the Rain, made after Hiroshige’s (1887) Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake (1857), because the subject of the discussion is not a matter of close copying, but further experimenting with new ideas.

However, there is a painting from Vincent van Gogh which magnificently represents his unique interpretation of Japanese irises painting. Emotionally van Gogh is very close too Japanese painters: he is very poetic and intense, while elegant.

“Irises”, Vincent Van Gogh, 1890, oil on canvas – on the left;

“Irises”, Ogata Kōrin, XVII c., ink and colour on gold-foiled paper- on the right;

Both artworks contain the same significant colours golden yellow, deep blue and green. Van Gogh outlined in black the irises petals, which bring a more dramatic and Asian effect, reminding ink and long thin lines of the Japanese.

It is relevant to examine new, heightened level of emotional condition, found in Japanese woodblock prints, via looking at images, depicting female facial expressions and body language. Gustav Klimt is famous for his female portraits, which are very direct and open in channelling women’s sensuality. I find a lot of the same emotion in the two iconic paintings below: “The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife”, Katsushika Hokusai, 1814, woodblock print; and “The Kiss”, Gustav Klimt, 1908-1909, oil, golden leaves on canvas; Both images are powerful in terms of reflecting woman’s emotion and sensuality. Both women are ovIerwhelmed by the possession of external force.

Another area in the figurative drawing changed is how westerners started to look in a new way and then emphasize women’s clothing. The Japanese did paint the dress with great attention to detail. However, their XVIII-XIX centuries’ drawings can still be considered high fashion. For example:

“Courtesan under a Cherry Branch”, 1800, Katsushika Hokusai, ink and colour on silk-on the left ;

“La courtisane Aimi de la maison Maruebi-ya flâne en compagnie de ses deux kamuro, Tsuruno et Kameshi”, XVIII-XIX, Utagawa Toyokuni I, estampe polychrome-on the right;

“Portrait d’Emilie Flöge”, 1902, Gustav Kilmt, oil on canvas; on the left below;

“Sur la plage à Trouville”, 1879, Claude Monet,oil on canvas; on the right below;

“The Child’s bath”, 1893, Mary Cassatt, oil on canvas; below on the left.

“Woman Bathing”, 1890-91, Mary Cassatt, oil on canvas; below on the right.

All these paintings bring women’s cloth to the canvas/ painted surface centre stage. Usually, they bring together a woman in her individuality, expressed via her cloth and a piece of nature, like skies, sea or sand, and cherry flowers. The bold and elaborate patterns contain strong stripes and geometric figures.

Conclusion:

Japanese visual art traditions indeed had a powerful effect on western painting evolution. Of course, the influence was mutual, but for this paper, I examined how new ideas in exotic visual art have been incorporated into western paintings and transformed traditional approaches toward modernism.

I think we should not underestimate the Japanese influence on the level of emotional intensity. It is worth to think about this influence not only in terms of technical aspects. Regarding technicality, Western artists, impressionists, symbolists and post-impressionists kept their mediums, methods and techniques: they continued to use mainly oils and canvas, and their brushstrokes stayed thick and wild. They didn’t borrow this fine and accurate linear approach or very defined details, which were common for Japanese drawings. They didn’t switch to inks to create many transparent layers in their landscapes. The main influence was not in technique or a new way to show perspective. I can assume that western artists were somewhat shocked by the exalted emotions they saw in Hokusai’a and other Japanese artists’ artworks. I observe a highly exalted emotion in snow, wind and rain, the roaring sea waves, the poetic tranquillity of landscapes with Mount Fuji, and scenes of sensual pleasures. The way the Japanese explicitly transferred a very human essence of very emotional beings to the surface of thin rice paper is still astonishing. Western artists saw Japanese visual art style as sensual in a different and new way. It was far from realism; it was intimate and delicate while bold in bringing forward a total subjectivity of individual experience. Therefore, it is not surprising that many western artists appreciated this purely poetic personal sense of self in a surrounding reality exquisitely transferred on paper.

@ZhanarSubkhanberdina July-August 2022

List of Illustrations:

Fig.1 Gustav Klimt,(1901-1902), Frise Beethoven, detail of central part, Les Puissance hostiles et Trois Gorgones. [mixed technique on stucco]. In: Metais, V. (2021) @Editions Hazan, p.17.

Fig.2 Katsushika Hokusai (1811/12), Tametomo and the Demons of Onigashima, silk painting. In: Mextorf, O.(2017) Könemann, by Ingrabar, Barcelona, Spain. p.76.

Fig.3 Katsushika Hokusai,(1811/12), detail of Tametomo and the Demons of Onigashima, silk painting. In: Mextorf, O.(2017) Könemann, by Ingrabar, Barcelona, Spain. p.77.

Fig.4 Katsushika Hokusai (1831/32), The Plate House, from the series One Hundred Tales, colour woodcut. In: Mextorf, O.(2017) Könemann, by Ingrabar, Barcelona, Spain. p.185.

Fig.5 Kawanabe Kyōsai (1883), Fantôme, silk painting. In: Christin, Anne-Marie (2021) Citadelles & Mazenod, Paris. p. 28.

Fig.6 Katsushika Hokusai (1830-34), Snow on the Nose in Settsu Province, colour woodcut. In:Mextorf, O.(2017) Könemann, by Ingrabar, Barcelona, Spain. p.94.

Fig.7 Katsushika Hokusai (1830-34), Moon over the River Yodo in Settsu Province, colour woodcut. In: Mextorf, O.(2017) Könemann, by Ingrabar, Barcelona, Spain. p.94.

Fig.8 Gustav Klimt (1916) Maison à Unterach am Attersee, oil on canvas. In: Metais, V. (2021) @Editions Hazan, p.37.

Fig.9 Gustav Klimt (1914-1915) Litzlberg sure l’Attersee, oil on canvas. In: Metais, V. (2021) @Editions Hazan, p.37.

Fig.10 Pierre Bonnard (1928) Landscape at Le Cannet, oil on canvas. At http://www.kimbellart.org/collection/ap-201801/ (Accessed on July 10 2022).

Fig.11 Vincent Van Gogh (1889) Landscape with House and Ploughman, oil on canvas. At http://www.reproduction-gallery.com/oilpainting/1067071700/landscape-with-house-and-ploughman-1889-by-vincent-van-gogh/ (Accessed on July 10 2022).

Fig.12 Katsushika Hokusai (1824-33) The Old Shrine in Shiogama and the Bay of Matsushima from a Bird’s -Eye View, colour woodcut. In: Mextorf, O.(2017) Könemann, by Ingrabar, Barcelona, Spain. p.212

Fig.13 Tawaraya Sōtatsu (beginning XVIII century) Cerisiers et corètes du Japon, ink on paper. In: Christin, Anne-Marie, Brisset, Claire Akiko (2021) Citadeles & Mazenod, Paris, p.84.

Fig 14 Anonymous author (XV) Fleurs et oiseaux des quatre saisons avec le soleil et la lune, ink on paper. In: Christin, Anne-Marie, Brisset, Claire Akiko (2021) Paravents Japonais, Par la brèche des nuages, Citadeles & Mazenod, Paris, p.94.

Fig.15 Claude Monet (1876) Le Parc Monceau, oil on canvas. In: Sefrioui, A, Monet, Edition Hazan, 2020, p.27.

Fig.16 Claude Monet (1884) Bordighera, oil on canvas. In:Sefrioui, A, Monet, Edition Hazan, 2020, p.33.

Fig.17 Vincent Van Gogh, ( 1890 )Irises, oil on canvas. At http://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/collection/s0050v1962/. (Accessed on July 10 2022).

Fig.18 Ogata Kōrin,(beginning of XVIII century), Paraventes aux Iris et aux Huit-Ponts, ink on paper. In: Christin, Anne-Marie, Brisset, Claire Akiko (2021) Paravents Japonais, Par la brèche des nuages, Citadeles & Mazenod, Paris, p.178.

Fig.20 Katsushiko Hokusai (1814) The Dream of The Fisherman’s Wife, woodcut, paper. At http://www.katsushikahokusai.org/Dream-Of-The-Fishermans-Wife.html/ (Accessed on July 12, 2022).

Fig.21 Gustav Klimt (1908-1909), The Kiss, oil on canvas, gold leaves. In: Mettais, V. Klimt, Editions Hazan, (2020) p.29.

Fig.22 Katsushika Hokusai (1800), Courtesan under a Cherry Branch, ink, colour on silk. In: Mextorf, O.(2017) Könemann, by Ingrabar, Barcelona, Spain. p.56.

Fig.23 Utagawa Toyokuni I (end of XVIII century), La Courtisaine Aimi de la Maison Maruebi-ya flâne en compagnie de ses deux kamuro, Tsuruno et Kameshi. In: Christin, Anne-Marie, Brisset, Claire Akiko (2021) Paravents Japonais, Par la brèche des nuages, Citadeles & Mazenod, Paris, p.22.

Fig.24 Gustav Klimt (1902), Portrait d’Emilie Flöge, oil on canvas. In: Mettais, V. Klimt, Editions Hazan, (2020) p.25.

Fig.25 Claude Monet (1870), Sur la plage à Trouville, oil on canvas. In: Sefrioui, A. Monet, Editions Hazan (2020) p.19.

Fig.25 Mary Cassatt (1893) The Child’s Bath, oil on canvas. At http://www.artsandculture.google.com/asset/the-child-s-bath/ (Accessed on July 12, 2022).

Fig.26 Mary Cassat (1890-1891) Woman Bathing, oil on canvas. At http://www.artsandculture.google.com/asset/woman-bathing/ (Accessed on July 12, 2022).

Bibliography:

The Art Story Foundation, s.d., Ukiyo-e Japanese Prints. At http://www.theartstory.org/movement/ukiyo-e-japanese-woodblock-prints/ (accessed 07/07/2022).

Callerame, E., (2020) “The Influence of Japanese Art on Western Artists” in: Artsper Magazine, 2020. At http://www.blog.artsper.com/en/a-closer-look/influence-of-japanese-art-on-western-artists. (Accessed 07/07/2022).

Chilvers, I., Doubt, E., Hildyard, A., Hodge, Susie., Kay, A., King, C., Zaczek, I. (2018), A Chronology of Art. A timeline of Western Culture from Prehistory to Present, London: Thames & Hudson, 2018.

Christin, Anne-Marie, (2021), Claire Akiko-Brisset, Torahiko Terada, Fujiko Abe, Pascal Griolet, Yōko Hayashi-Hibino,Paravents Japonais par la brèche des images, Edition: Citadelles & Mazenod, Paris.

Christina E., s.d. From Ukiyo-e to Modernism: How Japan Influenced The Next Generation of European Artists. At http://www.jpopexchange.net/from-ukiyo-e-to-modernism-how-japan-influenced-next generation-of european-artists.html/ (Accessed on 08/07/2022).

Google Arts and Culture, s.d., Japanese and Western Art Influences, at http://www.artsandcultutre.google.com/usergallery/japanese-and-western-art-influence/ (accessed 08/07/2022).

The Editors of Artsy.net, s.d., Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Japanese, 1797-1861. At http://www.artsy.net/artist/utagawa-kuniyoshi/. (Accessed on 08/07/2022);

The Editors of British Museum, s.d., Hashiguchi Goyo. At http://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BLOG1249/. (Accessed on 07/07/2022).

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica,(Mar 24, 2022)Treaty of Kanagawa, Japan-United States (1854). At http://www.britannica.com/event/treaty-of Kanagawa/ (Accessed 08/07/2022).

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica,(Jul 20, 1998), Utamaro, Japanese artist. At http://www.britannica.com/technology/letterpress-printing.(Accessed on 09/08/2022).

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, (Jul 20, 1998), Tōshūsai Sharaku, Japanese artist. At http://www.britannica.com/biography/Toshusai-Sharaku/ (Accessed on 09/08/2022);

The Editors Howard-Tilton Memorial Library, s.d. Online Exhibits, Japonism and Appropriation of Ukyo-e, at http://www.exhibits.tulane.edu/exhibit/copies-creativity-and-contagion/japonism-and-appropriation-of-ukiyo-e/. (Accessed on 08/07/2022).

The Editors of Joy of Museums Virtual Tours, Virtual Tours of Museums, Art galleries and Historic Sites, s.d., Goyō Hashiguchi-Japanese Woodblock Artist-Ukiyo-e. At http://www.joyofmuseums.com/artists-index/goyo-hashiguchi. (Accessed on 07/07/2022).

The Editors of Met Museum,s.d, Two Lovers. At http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/37123/ (Accessed on 09/07/2022).

The Editors of Portland Museum, s.d. Suzuki Harunobu. At http://www.portlandmuseum.org (Accessed open July 10, 2022).

Gombrich, E.H. (2014), The Story of Art, Moscow: Isskustvo-XXI, under license from Phaidon Press Limited, London;

Ferrand, Jean Luc, Mar 13 2019, The Japonism. At http://www.jeanlucferrand.com. (Accessed on 06/07/2022).

Folks, M., s.d., Japonisme:The Great Wave. At www. roningallery.com/blog/japoinism-the-great-wave-2/. (Accessed on 09/07/2022).

Forrer, M.,(2008), Hokusai- Mountains and Water, Flowers and Birds, München/London/New York, 2008.

Mettais, V.(2020),Klimt, @Editions Hazan, octobre 2020.

Mextorf, O.(2021) Hokusai, Barcelona: Ingrabar, Undustrias Graficas Barcelona.

Morrison, C. Feb 12 2019, Claude Monet and Japonism. At http://www.32minuteswordpress.com/claude-monet-and-japonism/. (Accessed on 10/07/2022).

Myers, N., August 2007, Symbolism, Department of European Paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. At http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/symb/hd_symb_htm/. (Accessed on 12/07/2022).

Richman-Abdou, K., June 12 2019, How Impressionism Changed the Art World and Continues to Inspire Us Today. At http://www.mymodernmet.com/what-is-impressionism-definition/. (Accessed on 05/07/2022).

Richman-Abdou, K., June 24 2022, How Japanese Art Influenced and Inspired European Impressionist Artists. At http://www.mymodernmet.com/japanese-art-impressionism-japonism/

Sefrioui, A.,(2020), Monet, @Editions Hazan, octobre 2020.

Taschen, B., (2021), Hokusai, Thirty Six Views of Mount Fuji, Taschen, Köln.

Tsoumas, J. 2017, “The Japanese Artifacts Display At The 1862 Great London Exposition: An Overview”, University of West Attica, Department of Applied Arts and Civilisation (Athens, Greece), at http://www.cyberleninka.ru/article/n/ (Accessed on 08/07/2022)

Below are some photos of my work in regress and the books I have used for this essay.

@ZhanarSubkhanberdina, August 2022;

Wonderful post.

japanese block prints

LikeLike